on clouds

We learnt about clouds in Grade 7, the only enjoyable part of school that year except getting my pen licence.

Cirrus: thin, wispy filaments composed of ice crystals that form at high altitude.

Stratus: flat, featureless sheets that develop low in the atmosphere, creating overcast conditions.

Cumulus: the kinds of clouds that children draw in blue crayon skies, with flat bottoms and cauliflower-like crowns; they drift low in the atmosphere and sometimes propogate into rainclouds.

Nimbus: dark, dense formations, associated with precipitation like rain, snow, or hail.

Little else of that year remains welded to my memory but a blooming sense of misery. I do remember, distinctly, the classmate who asked me where I was actually from, and I couldn’t tell if he was referring to my unplaceable accent, the result of having lived overseas for all my schooling so far, or my suddenly bushy hair, which I took to pulling back in a short, tight ponytail. I remember the grey trunks of the eucalypt trees and the sickly brown grass I could see from my bedroom window, so different from the vibrant lawn and coconut palms that stretched across our backyard in PNG. I remember being thrown off a horse and injuring my back, which got me out of our sports carnival – a blessed relief despite the pain, which left me shuffling around, inch by inch, and sitting on a doughnut-shaped cushion for weeks. I remember getting my period the week before my 12th birthday, eyes landing on the bloody gusset of my underwear, my first impulse to scream for my mum, who, in an unexpected reprieve from her unwavering never-miss-school policy, let me stay at home that day, where I sat miserably in a beanbag watching Oprah and mourning the death of my heretofore carefree childhood. (Why did girls in paperback novels always yearn for their periods? This – well, the canoe-sized pad my mother had dug out of her dresser drawer – was clearly the pits.) I remember all those afternoons at my grandma’s house after walking down the shoulder of the highway with my younger sister in tow. The school bus would drop us off at the servo next to the Black Forest Hill Cuckoo Clock Centre, and we’d languish in the dusty lounge room drinking glasses of sarsparilla or play with Lucy, Gimmy’s miniature fox terrier, until Mum picked us up after work.

But the clouds. The clouds. They’ve stayed with me the most.

The tattoo of a cloud beneath my right collarbone attracts comments and questions, so I usually keep it covered.

‘What does it mean?’ people like to ask of tattoos, and I often reply, of this one, that I simply like clouds. That much is true. Not wanting to appear twee or sentimental, I rarely mention that the birds in flight on my wrist symbolise freedom, some small celebration of surviving suicidal depression in my late 20s and early 30s.

The cloud, I think, is also a reminder of unboundedness and ephemerality.

This too shall pass, my grandma always used to say. Clouds are impermanent, always idiosyncratic, the confluence of particular and inimitable circumstances at any precise moment in time. They drift and reshape themselves as you watch. The human eye likes to find coherence: Doesn’t that cloud look like a dragon to you? Now a cartoon loaf of bread? A ballerina’s tutu?

The original Rorschach test.

There’s some obvious irony in having fixed something so cursory, evanescent to my body for good: one day I will be buried with it.

The journey between Brisbane and my hometown takes only an hour and a half, but it’s straight and unremarkable and intermittently terrifying because nobody obeys the fucking road rules. My husband, driving to retrieve me from my mother’s before a Covid lockdown some years ago, was almost killed on that highway when a drunk driver, travelling at approximately 150km/hr, rear-ended him in my little silver Mazda2, which I’d nicknamed Nimbus. What if what if what if what if what if, we thought for months afterwards.

I now cannot abide the journey between Brisbane and my hometown without some music or a podcast to listen to. It feels like a matter of survival. I’m worried I’ll nod off. I’m scared another driver will ram my car. So, I sip too-hot tea from a reusable cup, which I usually spill all over the console. I crack the window to test the temperature of the air outside (also too hot). I watch my rear-view mirror like a hawk. And I sing. Or I listen.

Driving back from my hometown last week following a medical appointment, I put on an episode of Bella Freud’s Fashion Neurosis in which she interviews Ocean Vuong.

I’ve recently begun a process of envuongification: two friends, whose tastes I trust implicitly, have waxed so rhapsodic about Ocean Vuong that I’m gradually succumbing, the way I usually do: from the outside in, paratext to actual text.

My envuongification has started with songs and podcasts. The books, I’m sure, will come in due course.

For now, I find myself delighted by the way Ocean can run with even the most flaccid or banal of stimuli and turn the conversation into something rich, thoughtful, and entirely unprecedented.

This podcast roves improbably over authorial style, heroin addiction (aka ‘pharmaceutical slaughter’), and Crocs (lol) all the way through to Buddhism and the writer’s ego. It’s the last part of the conversation that’s been orbiting my brain since I pulled up in my garage, the podcast perfectly timed for the trip.

Bella alludes with dismay to Ocean’s goal of writing only eight books. I emphasise ‘only’ because on this point, Bella and Ocean appear to be caught at crosshairs.

BF: I read that your plan is to only write eight books, and I have to say that made me feel distraught, as your work describes so much of the feelings I have that I find hard to handle, and… Do you ever change your mind about the things that you’ve decided?

OV: Of course, you know, you transform. I think that’s the hope, you know. If I’m very lucky I can get to eight works. I mean, I’ve written four, and I feel knocked flat. Like, I feel like the way I’m sitting, laying on this couch now. I feel just as horizontal as I can be, you know. But that would be… that’s the fantasy, I think. To be able to… And it’s an arbitrary number, after the Eightfold Path.

But the fantasy is to one day do one’s work with such care that one can look at it and say, ‘Well done.’ And one can have a life, maybe moving into a different medium. But to finish. I don’t think any medium can be exhausted. But to lay down your work. And again this is a very Buddhist idea. Everything about Buddhism is about ephemerality. And I don’t want to be attached to the idea of being a writer. You know, it’s very seductive to be so lauded for one thing. And then it becomes… you become attached, the ego becomes attached to this idea that I am writer, writer, writer.

I look forward to the day that I can disabuse myself. I can take that outfit, if you will, out and again go back to being naked and still have my body. And what will I feel? What will I look like if I still had my life while taking away something I’ve spent so many decades on and leaving it behind? It’s a very important practice, which is why monks shave their heads. They’ve left… They disrobe, right? Taking idiosyncrasy away that you’ve been so proud of and taking on something else. So, in a way, stopping writing is a kind of disrobing for me and taking on another pair of robes. To me, it’s a very spiritual practice that I hope I have the strength and the effort to do.

It’s interesting to me that Bella conceives of eight works of literature as a modest goal while Ocean’s perspective is that eight is a lofty – and worthy – goal to aim for. Perhaps the disjunct in their thinking comes from a growing expectation in publishing of almost limitless proliferation. Ocean is a notoriously, purposefully slow (by his own definition) writer. I love this idea of separating oneself from the hubris of publication.

The idea of the body-self goes back to something else he explains:

OV: I’m not attached to the idea of me, Ocean Vuong, being glamorous, but I’m attached to mapping myself on to the conditions. Thich Nhat Hanh talks about this – that our lives are like clouds. A cloud looks robust and real and palpable, but it doesn’t come out of itself. It comes out of conditions.

I find it true, to some extent, that ‘being a writer’, whatever the word really means, likewise arises from certain conditions. Some you can control. Others you can’t. Maybe it’s healthily freeing to shed the mantle of WHATEVER as identity. At university, I was told that if you write, you’re a writer. There is no other condition.

But maybe there’s another possibility. Just write. Be nothing.

In Melbourne back in September, I stumbled across a hardback book all about clouds.

I’d told my cousin I’d meet him at The Paperback Bookshop on Bourke Street, which is the kind of bookstore I’d own if I had the smarts and fortitude for retail. I’d recently found out I was pregnant, and as I sat on a footstool to pass a wave of intense nausea, my eye landed on this purple canvas cover, a shade reminiscent of the jacaranda flowers about to blossom in Brisbane, heralding the start of Exam Season.

Later, in a café where he was assessing the cookie quality, my cousin asked me to show him my book bounty, paltry as it was on account of my having carry-on luggage only for the flight home.

‘Why clouds?’ he asked. ‘I just like them,’ I replied.

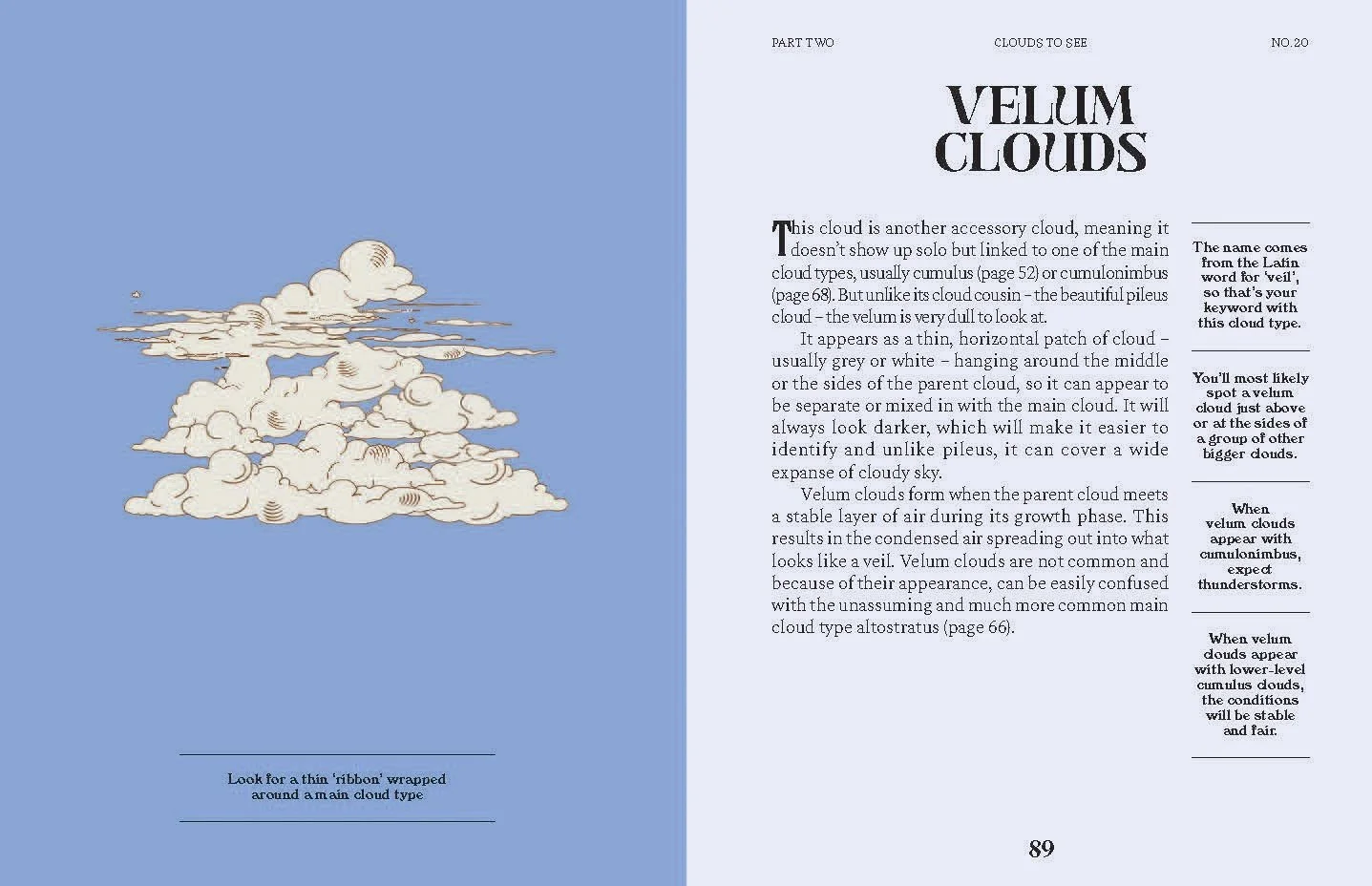

Clouds: A Guide for the Curious by Susan E. Clark is part of Quadrille’s nature series. It’s not quite pocket-sized, but it’s small enough to be considered dinky. Inside are two parts. Part One is all about manifestations of weather, including clouds, of course, but also phenomena such as rainbows, fog, tornadoes and twisters. Part Two spans descriptions and illustrations of 30 different cloud types, each as gorgeous as the next.

Clark writes in the introduction: ‘Clouds have captured the imaginations of weather scientists, poets and painters alike since the dawn of time. There’s something about the transience of a cloud pattern that reminds us that in life, everything is about flow, and nothing stays the same.’

Everything and nothing has changed since then.

This book sits on my bedside table.